Help your doctor be a better doctor

We all know that the health care industry in the U.S. is sick as a pup, but no one can agree on the reasons, and no one agrees on the cures. At the national level, it’s a complex crisis.

At the personal level, health care providers’ compassion is being eroded by time crunches, perverse incentives, and the pressure to tick certain boxes on the billing profile to shift their focus from people to profits. Despite the advances made by the wonderful mid-level providers (whom I include as “doctors” here), personnel shortages in key areas will continue to stress an already stressed system.

Patients are suffering as well. Even if we have access to health care, our visits to the doctor are often difficult, frustrating, or contentious. For people with chronic illness or disability, it is worse by orders of magnitude. While we wait for the miracle that health care reform would surely be, I believe we can at least improve our own and our families’ experiences and outcomes. To do that, I want to prescribe a few basic tactics and some attitude adjustment.

How it usually goes

Here’s what usually happen when you get sick in America.

First, you live with the pain or the rash or the twitch for as long as you can, trying every remedy you can think of, including Dr. Google, who can see you 24/7 but is not a good listener.

Finally, you cry uncle and go to whatever real doctor is in your “plan.” (If you are lucky enough to have a “plan.” No plan? Keep living with the pain until it sends you to the Emergency Room.)

When you get to the doctor’s office, you try to communicate both your worries and your modest expectations. You hope the doc can confirm-or-rule-out whatever you think is wrong, and then give you a note that excuses you for missing work. And maybe a Z-pack.

And you say all this in a rush, because you know that a typical visit will barely last 12 minutes, and that the doctor will probably interrupt you an average of 17 seconds into the consultation.

What next?

What are the possible outcomes? Best case: the doc declares that it’s nothing, but praises you for coming in because it could have been something. Next best scenario: the doc tells you it’s nothing, and also implies that you were a fool to be so worried. Either way, they bill you, but you’re just glad you’re all right.

Jackpot scenario: The doc believes it IS something, but you wisely caught it in time, and there’s a reasonable and affordable treatment plan that should take care of it. Score! You’re usually so glad for this assessment that you’ll do whatever you’re supposed to do for as long as you’re supposed to do it.

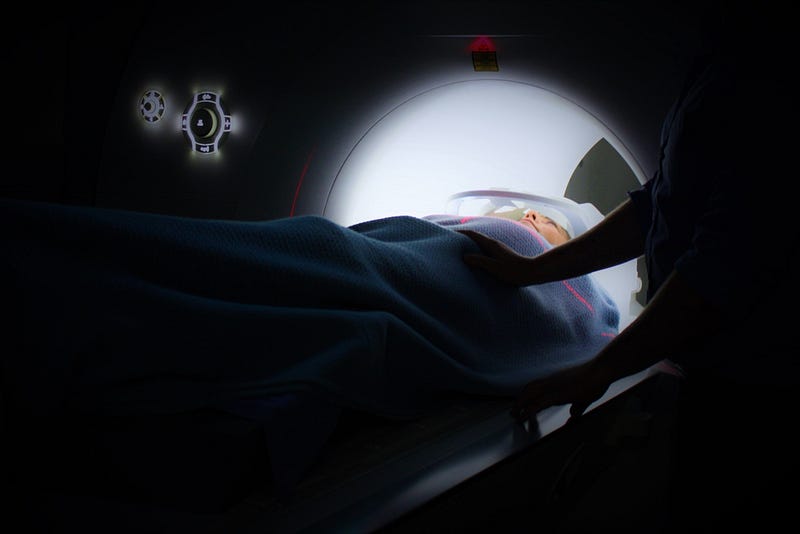

Least favorable scenario: You have a real problem that needs immediate treatment, and you are now entering the world of specialists and surgeons and medicines and machinery and financial coordinators. “At least,” you pluckily tell yourself, “at least I know what I’m up against.” If that’s the case, then bless you, and please read on, because you will need these tactics more than ever.

Classic doc moves

Doctors need to check all the boxes when doing an exam, and many of those have to do with giving doctorly lifestyle advice, such as “Eat more fiber.” You may be advised that ALL of your Lifestyle Choices are wrong. So: Stop smoking. Reduce stress. Lose weight. Exercise more.

Ah! Exercise! That’s the all-purpose scapegoat these days. (It used to be smoking, remember?) If you don’t exercise (maybe because you’re, well, sick) they will tell you to start. If you do exercise, they will tell you to exercise more. However, if you already follow a great exercise program, and you get sick anyway, the doc will quickly change the subject.

It’s an article of faith: Exercise prevents illness.

Except when it doesn’t.

I’m all for educating patients about improving their own wellness, but I’m not in favor of blaming them for being sick. First, what if they just got crappy genes in the ongoing evolutionary lottery? And what about the unhealthy jobs, or the ubiquitous junk foods, or the bad air, or the lead-laced water? What about the noise and traffic and anxiety that assault us practically everywhere we go, or the broken health care system itself? Rather than addressing those conditions with appropriate public policy, we’d rather criticize the single parent with two jobs for not going to hot yoga. Or yoga with goats. Or whatever.

Seven things you can do

It does look dire right now. But since I want to promote action, faith, and hope — here are some reminders of what we CAN do to improve our outcomes when we venture in to the doctor’s office.

First: You do you.

Take ownership of the way you treat your body without allowing yourself to be blamed for your illness. Ideally, your compassion for yourself will motivate you to care for yourself as best you can. But the healer is there to heal, not to judge.

Second: Get your homework done.

Do that annoying, repetitive paperwork in advance, if you possibly can. You will be less flustered, your answers will be more thorough, and your handwriting will be neater. Plus you won’t have to handle that germ-covered clipboard in the doctor’s office.

Third: Remember you are a person, not just a patient.

I dislike it when office staff call me by my first name, like a child, when I am already in a vulnerable state. I’m speaking up about it now, insisting that I be called by the name I prefer. I have to tell them over and over, so now I’m going to ensure that my preferred name is written in big block letters on top of that paperwork I am filling out. You, too, have the right to be called by any name you choose. (And by the way — privacy laws do NOT require the staff to call you by your first name only. Tell them to look it up, for crying out loud.)

It may seem warm and fuzzy and egalitarian to call your doctor by their first name — and perhaps they will even ask you to do so. But in most circumstances, I suggest it’s healthier to remember the doctor’s proper role in your life. YMMV.

Fourth: Make time for the Q & A.

Make a list of your questions — you’ve heard this before. But then you have to use it. Ask each question and make a note of the answer. And don’t be rushed. You’re saving time by preventing that lame call to the office later, when you have forgotten what they told you. (And you will forget. Doctors’ offices have powerful amnesia-producing machinery built into the exit doors.) Even simpler: record the consultation with your phone. I don’t know why I haven’t been doing that all along.

Fifth: Use your words.

Once you are telling your story to your doc, don’t bury the lede. In your precious minutes with your doc, start with your most important concern. Too often, we nervously try to build up to our main concern: “Well, it all started about six months ago, let’s see, right after the dog died…”

No. That’s how you tell things to your friend, not to your doctor.

Instead, when the doctor comes in and asks, “How are you?” don’t say you’re fine. That’s ridiculous. Say, “I am hurting, I’m scared I have cancer, and I need you to help me figure it all out.” You don’t need to go full “status dramaticus,” but you do need to give the doctor straightforward information, right up front.

It feels awkward at first, and you may have to practice. But doctors are not mindreaders or priests, and it’s been shown that they often fail to respond empathetically to the subtle emotional cues we send out.

However, your doctor will most likely respond by trying to solve the problem that’s causing your distress. And that’s really the goal, isn’t it?

Sixth: Keep your own records.

Keep your own medical records, because it’s amazing what we forget: Which relative had what disease? When did I have that surgery? What medication worked and which one gave me that embarrassing rash? You’re a grownup now, so everything’s Going On Your Permanent Record.

Seventh: Bring a ride-along.

Bring someone with you, for heaven’s sake, for anything but the most routine of visits. Then you return the favor, if you can. Even though you may have a friendly, familiar, and helpful doctor, you are also dealing with a complex health care system, and not from a position of strength. You need an ally, and sometimes an advocate. Or just someone to help pass the time in the waiting room, when you are tired of looking at the fish tank or the television news you couldn’t care less about at the moment.

And work toward change for everyone

By doing your best to manage your health care prudently and proactively, you can transform the experience you have with your provider. If not, then you may at least feel empowered to look elsewhere for a doctor that suits your needs better. It’s all right to do that.

At the same time, I believe we need to improve the health care delivery system for everyone, so that doctors don’t have to be merely “providers” for profit, but can reclaim their original desire to be healers.

Improving health care for all of us is a matter of enlightened self-interest for each of us. We have public education because pragmatists realized they did not want to be surrounded by uneducated people. Similarly, I want all people, both the differently-abled and the temporarily-abled, to be able to live their best lives, contribute their best society, and not cough germs in my face at the mall.

There is so much more to say about this national crisis. But I’ve been sitting writing this for hours, so now I really need to get some exercise; maybe do some yoga or something.

Leave a comment